Understanding Toolchains for Cross Development

What is a Toolchain?

A Toolchain is literally a collection of tools for Cross Development.

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

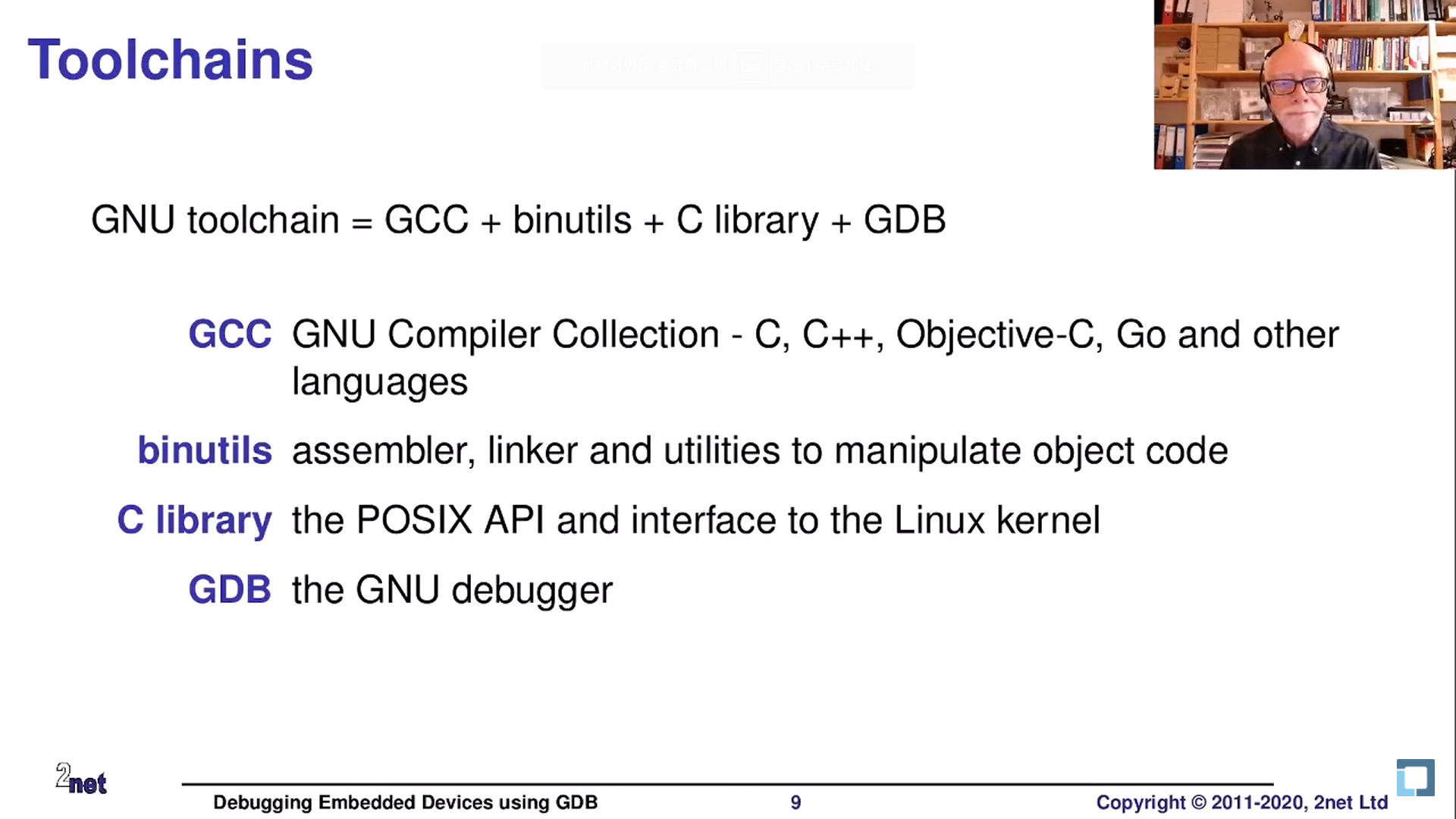

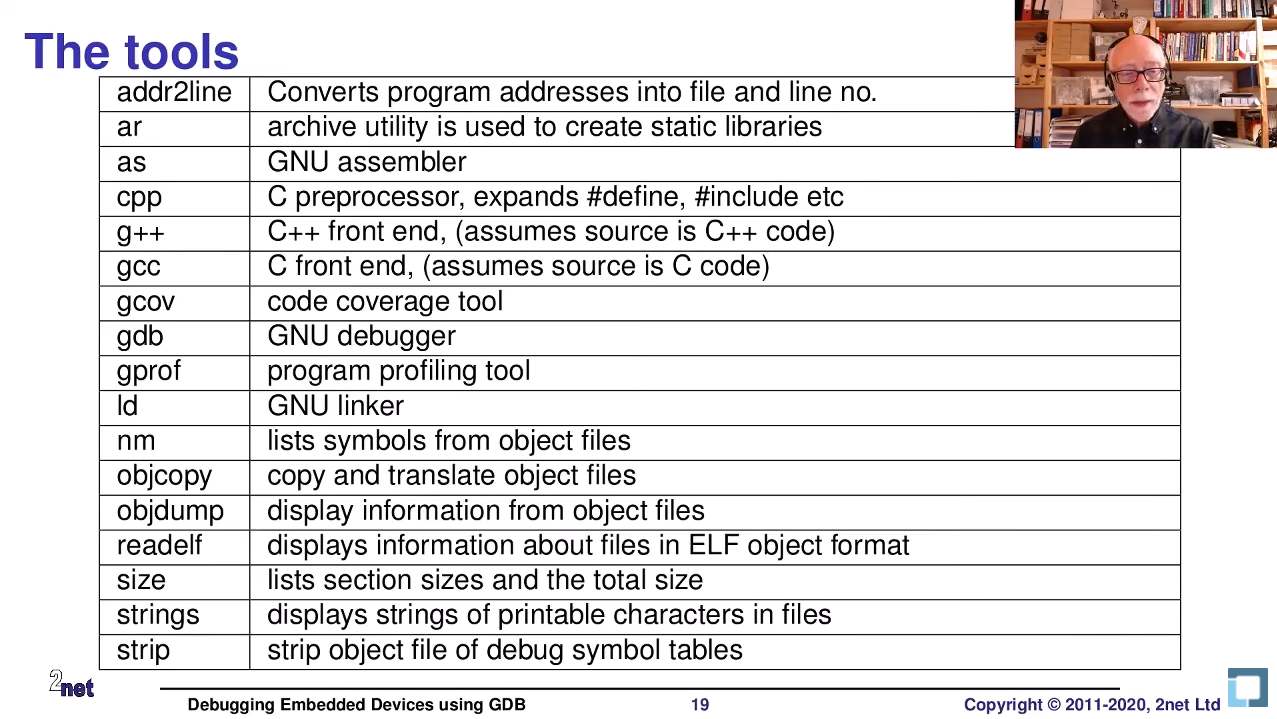

As shown in the diagram above, the GNU Toolchain is broadly divided into compiler, binutils, C library, and GDB debugger.

- Compiler: A tool for compiling from the host development environment to the target architecture

- binutils: Assemblers, linkers, etc. for controlling compiled objects

- C library: POSIX and Linux kernel interfaces

- GDB: GNU debugger

Getting a Toolchain

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

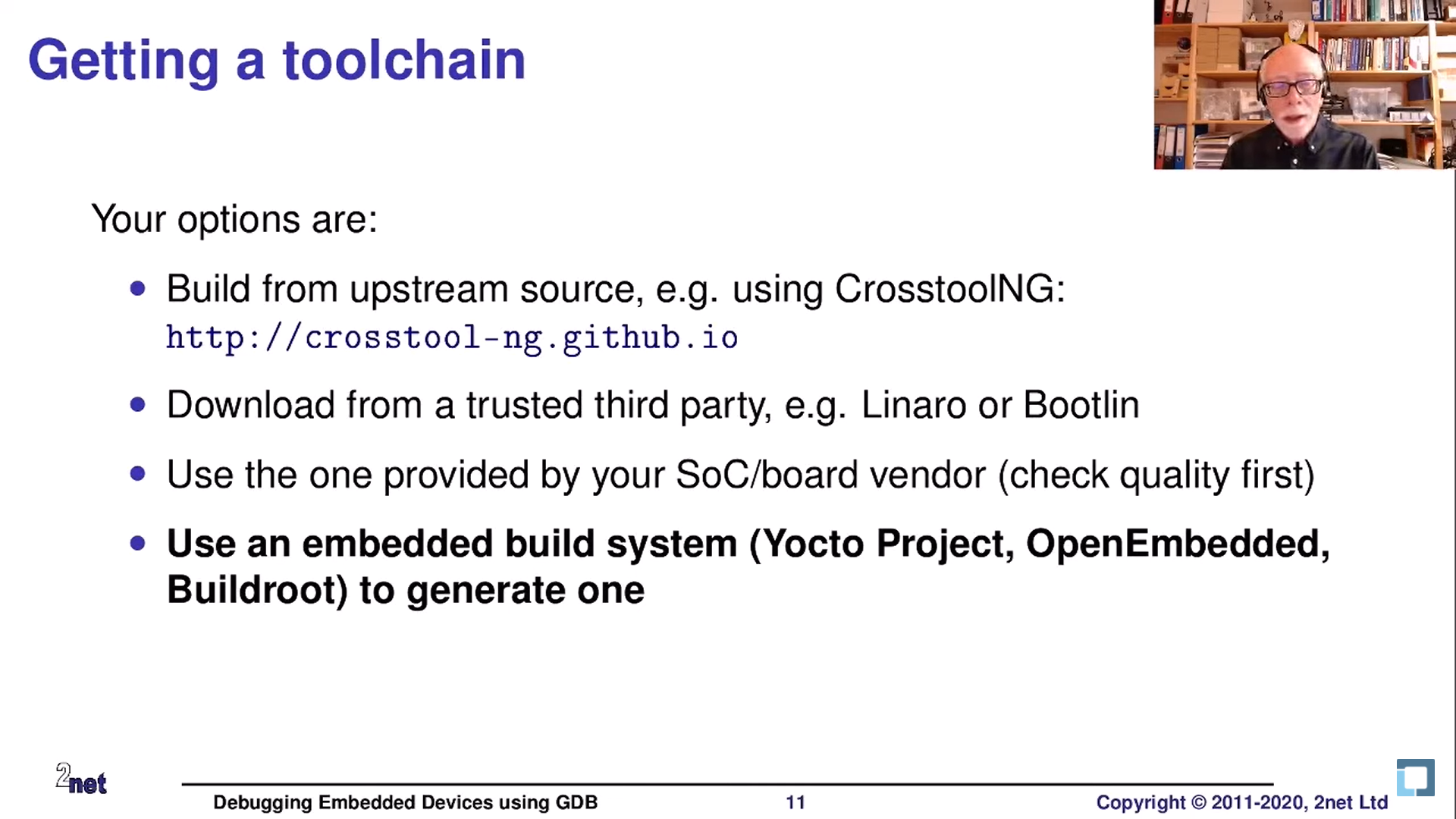

As shown in the diagram above, toolchains are usually provided by chip manufacturers. Alternatively, you can download them from famous third parties like Linaro, or get them conveniently using build systems like the Yocto Project.

Toolchain Prefix

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

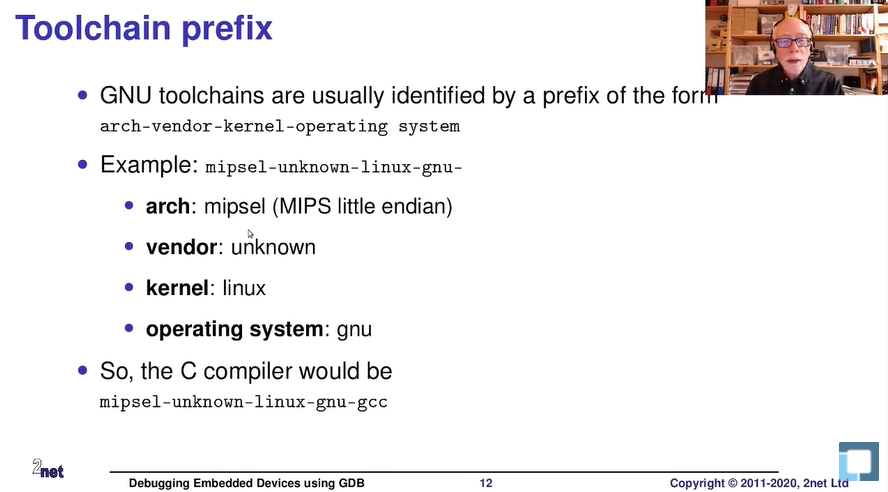

Let’s look at the toolchain naming rules through the diagram above.

They’re separated by ”-” and named in the order “architecture-vendor-kernel-OS”.

Toolchain Prefix for ARM Toolchain

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

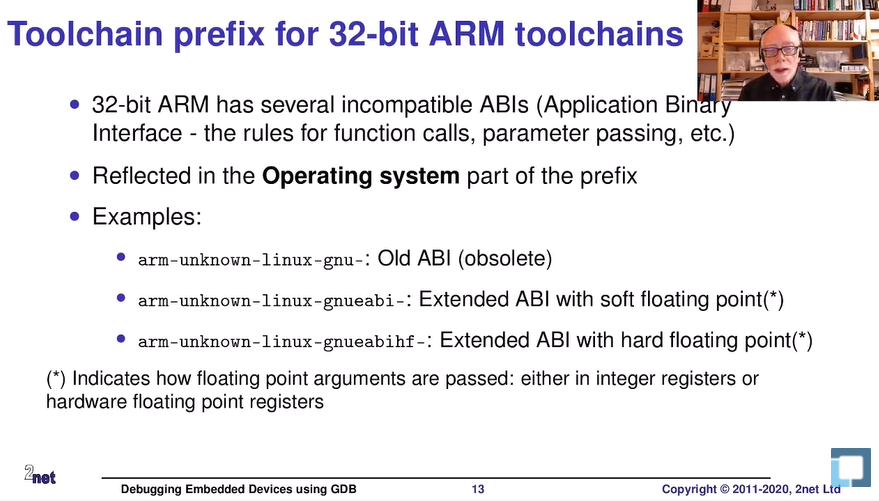

I mentioned above that toolchain naming ends with the OS. Additionally, the ABI (Application Binary Interface) gets added to this.

This tells us the rules about how the target OS exchanges binary data between applications.

- Data types and alignment methods

- How to exchange registers for arguments and results during function calls

- How to make system calls

- How to initialize program code start and data

- How to exchange files (ELF, etc.)

As shown in the diagram above, old (or obsolete) ABIs omit the suffix after the OS. This was used during the era when 32-bit ARM architecture was supported.

Starting from EABI (Embedded ABI), it was created to support 64-bit architecture in embedded environments (ARM, PowerPC, MIPS, etc.).

If you just use eabi, it’s softfloat, but if you add hf to make it eabihf, it becomes hardfloat. The differences are as follows:

-

softfloat

- Doesn’t create FP instructions; GCC prepares them as functions in libraries at compile time

-

hardfloat

- Emulates FP instructions

A CPU like the ARM can do calculations. In most programs most of these calculations are of the “whole numbers” (integer) type, as these are very simple to do electronically. Some programs also do “floating point” calculations, and these programs also are expected to work on CPU’s that do not have the hardware to do floating point calculations. In such cases these calculations are automatically routed, by the operating system, to a library of calculation routines that do these calculations using integer calculus. For example a simple division like 2/3 is done with hundreds of integer calculations. This is called “software floating point calculus”, or short “soft float” But the ARM chip has a CPU that can also do floating point calculations directly in hardware! This happens very much faster, as a floating point calculation in hardware is almost as fast as a integer calculation. hardware floating point calculus is shortened to “hard float”. In the past the R-PI’s operating systems did not “know” the R-PI’s CPU could do floating point calculus, so all floating point calculations were done using the software library. With the latest OS’s they became “aware” of the hard float capability of the PI and began using it, which means a very big speed increase for programs using a lot of floating point calculations.

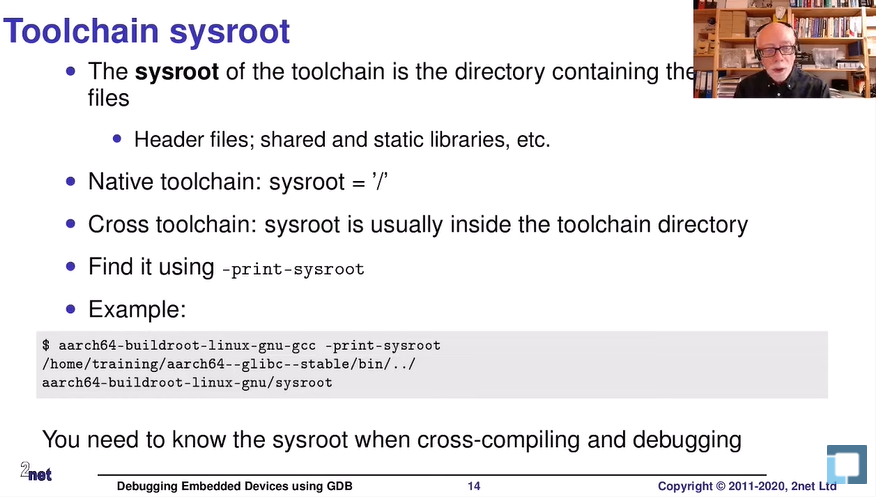

Toolchain Sysroot

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

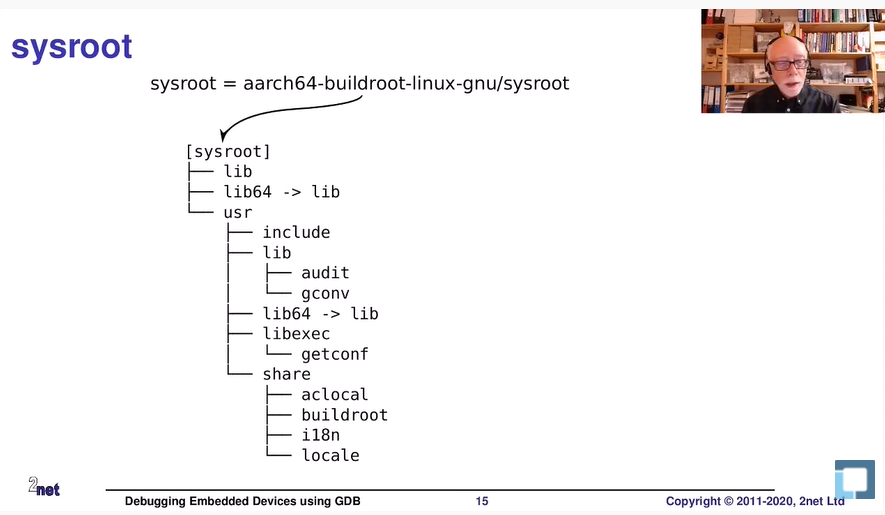

Sysroot refers to the rootfs that will actually be present in the target environment.

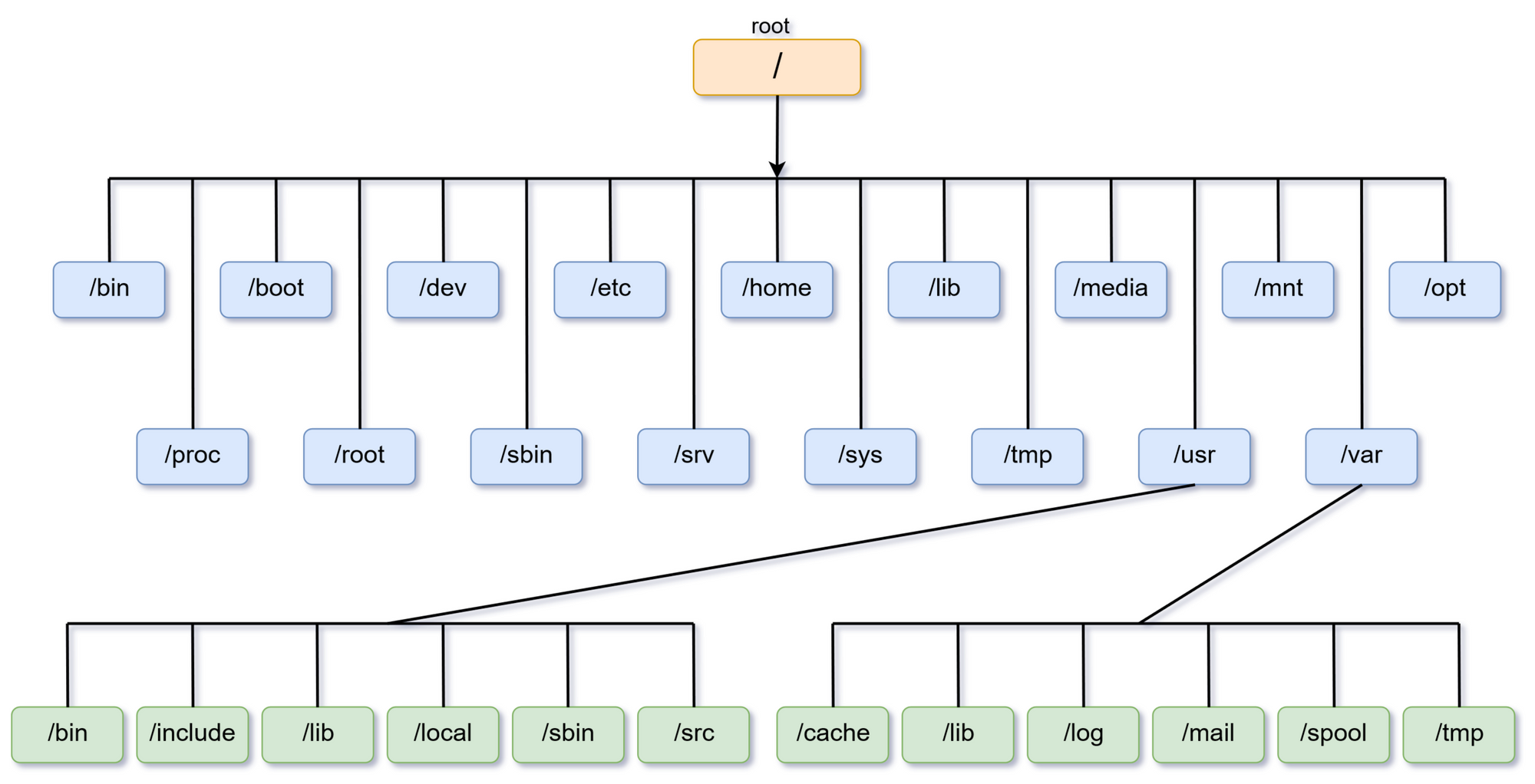

Linux rootfs

Linux rootfs

The root file system (named rootfs in our sample error message) is the most basic component of Linux. A root file system contains everything needed to support a full Linux system. It contains all the applications, configurations, devices, data, and more. Without the root file system, your Linux system cannot run.

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

You don’t need everything in that target environment - just some parts for cross-development.

For example, libraries and header files.

What Toolchain Contains

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Example

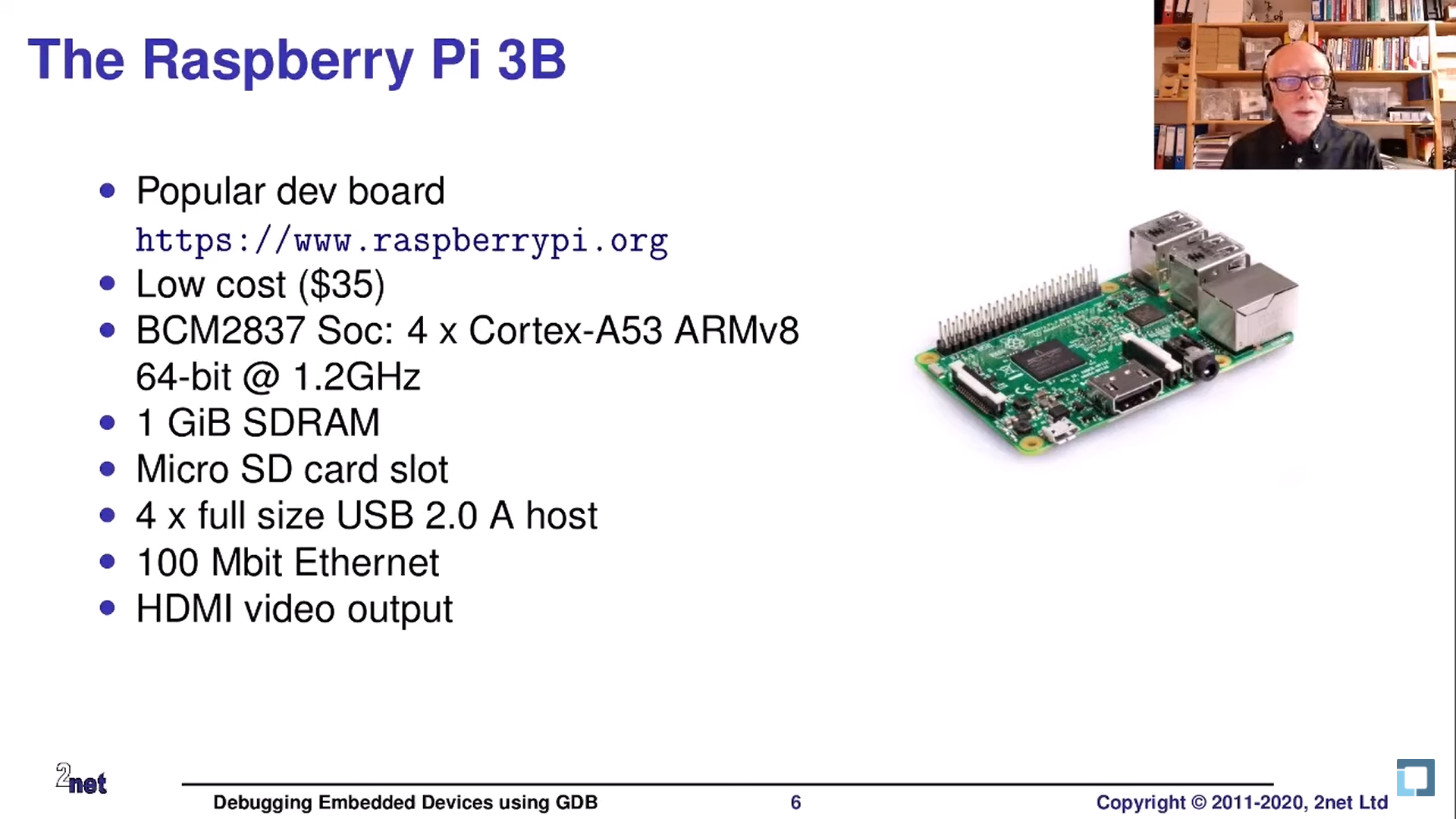

Let’s assume we’re developing with Raspberry Pi as the target.

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

Ref: Linux Foundation 2020 Conference

These days, they’re called SBCs (Single Board Computers) and have performance that wouldn’t be embarrassing to call computers even if we go back just 10 years. But embedded devices are still embedded devices - they don’t match our host computer performance, and the goal of the device isn’t to replace PCs, right? I’m getting a bit off-topic here. Haha;;

The official toolchains for the Raspberry Pi 3B model are the following 6:

- arm-bcm2708hardfp-linux-gnueabi

- arm-bcm2708-linux-gnueabi

- arm-linux-gnueabihf

- arm-rpi-4.9.3-linux-gnueabihf

- gcc-linaro-arm-linux-gnueabihf-raspbian

- gcc-linaro-arm-linux-gnueabihf-raspbian-x64

Do you see the common patterns in these names?

This sequence is usually called a Triple.

These days, <arch>-<vendor>-<kernel>-<os> is the basic rule, and they seem to modify it a bit here and there. (I need to research this more.)